The Intersection Between Race and Place

My colleague Ebony Walden uniquely positions her life’s work as critically examining the intersection between race (& racism) and place. As an African American urban planner, such a focus makes imminent sense.

When she shared this with me some years ago, I realized that although my consulting work has not served as a critical examination of that intersection, the legacy of racism, discrimination, and oppression has shown up in nearly every important community engagement project I’ve done. Those legacies were not always acknowledged or named and weren’t addressed in ways to repair past and current harms. But the painful legacies persisted.

What do I mean?

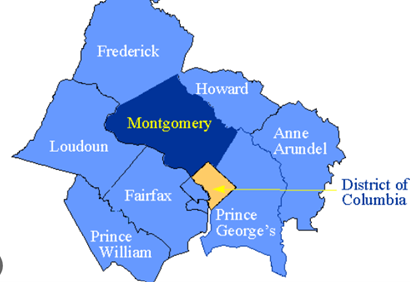

Many of my projects with my firm, Public Engagement Associates (PEA), in the past two decades—and nearly all in the past ten years—have occurred in the metropolitan Washington, DC area. In our work, we facilitate constructive conversations with community members and other stakeholders to provide input and guidance to locally elected officials and policy-makers as they craft new policies, develop new plans, or look to pass new legislation.

Many of the legacy issues in these urban areas connect directly to redlining—and its predecessors—that made racial, residential segregation a permanent fact of life for nearly a century in America. The Black ghettos that White leaders created across the nation in the early 20th century hardly dissipated once the Fair Housing Act outlawed redlining in 1968. Thus, cities in my region like Washington, DC, Baltimore, MD, and Richmond, VA—and many of their inner suburbs—wrestle with a host of issues that this ‘ghettoization’ set in motion.

They continue to set too many African American members back.

Food deserts (also known as food apartheid), health care deserts, close proximity to polluting and toxic waste facilities, low-quality and low-performing schools, neighborhoods with few of your standard, quality amenities (e.g., parks), not to mention higher areas of crime all hold these communities back.

Public Engagement Associates has worked on projects where these legacy issues show up prominently, including:

In the District of Columbia

Washington D.C.’s comprehensive plan efforts in 2006 and the 2018 update focused on creating a more inclusive city. The vision for the 2006 plan was for “growing an inclusive city,” focused on developing successful neighborhoods, increasing access to education and employment, and connecting the whole city. Yet, by the time the city was ready to update the plan 12 years later, implementation had not only fallen far short of those goals, but the wealth and income divides had grown wider, and more than 20,000, predominantly lower-income, Black residents had been displaced from the early 2000s to the late 2010s.

Washington D.C.’s comprehensive plan efforts in 2006 and the 2018 update focused on creating a more inclusive city. The vision for the 2006 plan was for “growing an inclusive city,” focused on developing successful neighborhoods, increasing access to education and employment, and connecting the whole city. Yet, by the time the city was ready to update the plan 12 years later, implementation had not only fallen far short of those goals, but the wealth and income divides had grown wider, and more than 20,000, predominantly lower-income, Black residents had been displaced from the early 2000s to the late 2010s.

District leaders looking to implement Mayor Vincent Gray’s One City agenda from 2011 to 2014 found great difficulty deploying the right strategies to bridge the economic and social divides between Wards east of the Anacostia River (7 and 8) and the rest of the city. Even when we helped the Mayor to convene two economic development summits, one with Ward 7 residents and the other with residents of Ward 8, the priorities set there found limited fertile ground in a city accustomed to ignoring the realities “east of the river.”

In a project we did with the D.C. Bar Foundation, we facilitated meetings to help multiple pro bono legal aid organizations provide a more coordinated and systematic approach for tenants facing eviction-related, court-related proceedings. It became clear how many lower-income residents—almost always Black or Latino—faced such proceedings throughout the calendar year, primarily due to ongoing economic and financial constraints they experienced as rents rose annually.

In Prince George’s and Montgomery Counties, Maryland

In our work with the Purple Line Corridor Coalition (for a new surface transit line connecting these two local Maryland counties), we’ve seen the risks of displacement that many underserved communities face along the line (primarily immigrant, but also African American). Many of the neighborhoods throughout the corridor are poised for near-term gentrification. The coalition is working aggressively to ensure significant new affordable housing is built along the line while directly supporting dozens of BIPOC small business owners to deploy strategies to survive (and hopefully, eventually, thrive). But it’s far from guaranteed that a cross-sector coalition can prevent displacement in any significant way.

In our work with the Purple Line Corridor Coalition (for a new surface transit line connecting these two local Maryland counties), we’ve seen the risks of displacement that many underserved communities face along the line (primarily immigrant, but also African American). Many of the neighborhoods throughout the corridor are poised for near-term gentrification. The coalition is working aggressively to ensure significant new affordable housing is built along the line while directly supporting dozens of BIPOC small business owners to deploy strategies to survive (and hopefully, eventually, thrive). But it’s far from guaranteed that a cross-sector coalition can prevent displacement in any significant way.

We’ve seen a similar dynamic in our engagement work with stakeholders along Prince George’s County’s Blue Line Corridor. The many working-class neighborhoods are girding themselves for significant redevelopment activity that will lead to gentrification and displacement pressures for African American residents and minority small business owners alike.

PEA has also been involved on the consultant team to help both school systems determine how to redraw boundaries. In Montgomery County, we heard White (and some Asian) parents objecting to boundaries getting redrawn where it would require their children to attend school “with those kids,” meaning predominantly Black and Latino kids living and attending school in working-class neighborhoods. We also heard White parents complain that they purchased their expensive houses in expensive neighborhoods so their kids could go to the best public schools in the county and that changing boundaries would jeopardize that investment.

Many of the neighborhoods these White parents referenced have, throughout history, been exclusively—and remain—predominantly White, originally due to redlining. The comments of these White residents demonstrate how much place still matters in our lengthy, post-redlining era and reveal how places greenlined (for investment in White neighborhoods) and redlined back in the 1930s continue not only to divide and separate us but also play a significant role in sustaining our racial income, wealth, and homeowning divides.

Many of the neighborhoods these White parents referenced have, throughout history, been exclusively—and remain—predominantly White, originally due to redlining. The comments of these White residents demonstrate how much place still matters in our lengthy, post-redlining era and reveal how places greenlined (for investment in White neighborhoods) and redlined back in the 1930s continue not only to divide and separate us but also play a significant role in sustaining our racial income, wealth, and homeowning divides.

AND In Fairfax County, Virginia

In a meeting we facilitated in Spring 2023 in Gum Springs, a small, historically working-class African American enclave in wealthy Fairfax County, we heard from scores of Black Gum Springs residents who had felt consistently disrespected over many decades by a White-led and majority White county. Most recently, in the 2010s, this disrespect involved the community feeling totally ignored when the members had proactively developed a conservation and historic preservation plan for Gum Springs that addressed chronic, blighted community conditions and adverse development threats—which the county never implemented.

Summary

I could list a dozen more project examples beyond the above. Community engagement is essential to local democracy as it gives community members a voice in their present and future. But community engagement that leads to equitable change is only possible if the conveners—not the facilitators—of the policy and planning conversations have framed these opportunities to give “voice” in ways that provide a genuine pathway to equitable change and a more equitable future for those communities.

Image of D.C. courtesy of ChatGPT.